It had been a winter of Saturday and Sunday afternoons spent at local museums, libraries and bookstores. With my two-and-a-half year-old daughter in tow, I’d regularly counted on these institutions to occupy us during that best part of the week: idle weekend afternoons. But the weather was warming and the steady spring breeze fresh with lilac and honeysuckle beckoned us outdoors. And, it was baseball’s opening weekend.

Understand I grew up riding a hand-me-down campus green Schwinn Sting-Ray all over town. Like my friends, I carried a Louisville Slugger across the top of the handlebars, the right grip tucked securely through the strap of my mitt. During summer break, I’d pedal off to the dusty sandlot and Little League fields of my youth.

As an adult that had just spent the winter trying to reconcile feelings of anger, frustration and fear following fall 2001’s dark events, I was ready to reignite my passion for America’s pastime. I was ready to revisit an impactful game I’d learned well as a kid prowling northwestern Ohio’s ballparks.

Was my daughter ready for it, I wondered? Would she have the patience to sit through three or four innings, which would make driving downtown, buying tickets and battling a small crowd worthwhile?

I decided to give it a go. I packed her, along with a child-sized backpack. Tucked inside were the essentials: a blanket, juice cup, suntan lotion, diaper, wipes and goldfish crackers. Then it was off to Slugger Field, home of the Cincinnati Reds’ AAA affiliate Louisville Bats.

Because my family moved to Kentucky when I was in high school, Louisville became the center of my adult life. What’s ironic is I moved from Toledo, home of the Detroit Tigers’ AAA affiliate Mudhens, who would prove to be the spoiler to Louisville’s excellent 79-65 run through the International League’s West Division that year. The Mudhens would make it to the post season, the Bats would not.

Optimism is prevalent on opening day, though. We found a parking spot just near the stadium. Back then I used to just turn left out of our subdivision and take Louisville’s scenic River Road, which provided a stress-free journey downtown, all the way to the ballpark. Before the city began insisting you queue in traffic to enter a $20 surface lot, I could just park free right on the street.

I only needed to carry the kiddo an easy block to the box office. At Slugger Field, there’s a ticket booth located conveniently behind left field. All you need is your ticket and to climb two flights of stairs and there you are.

Arriving at a ballpark should always be an electric experience, as should the first time you see a stadium’s perfectly manicured field and meticulously prepared diamond. Yet, it’s easy to overlook the sensation on subsequent visits, especially in our “event presentation industry” age in which loud music, gaudy lighting, massive video boards and, of course, the ubiquitous smartphone, are always buzzing, blinking and chirping for your attention.

Hannah’s immediate reaction was encouraging. Approaching the stadium, sensing the energy and head on a swivel, she tuned it all in: fans lining up to enter, the ballpark’s music and PA announcer’s voice carrying over the brick walls, flags and pennants waving with the wind, the pungent smell of meaty hot dogs and sweet and savory onions wafting in the breeze and a sweating man surreptitiously striving to capture our attention.

It was my dad who modeled buying from scalpers. He once bought tickets from a shady seller just outside Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. The first gate keeper turned our tickets away, leading to skepticism we possessed legitimate entry, but someone soon directed us to the press entrance, where we enjoyed seats boasting a great view.

I guess that’s why I didn’t hesitate to walk up to this guy buying and selling tickets within twenty feet of the box office despite ticket scalping being illegal in state. Turns out he wasn’t necessarily scalping, per se, but buying and selling extra or abandoned tickets. He offered a box seat for just five bucks. Face value was eight. All I had was a ten. “No problem,” he said, counting off five ones from a roll produced from the same hand holding a stack of purple-edged tickets. I asked about a second ticket for Hannah, figuring she’d want her own seat. He just shook his head. “Nah,” he said dismissing me, turning to locate his next sale. “They’ll let her in without one.” And off he went.

We waited in line, passed through the turnstiles, then ascended twenty or so wide and bright concrete steps. Climbing the last four incrementally improved our view a few feet at a time. Entering a stadium through a tunnel or up a ramp does that. The walls drop away as the lush green grass and deep brown dirt of the diamond mix to form special grounds right before you. Ballparks are sometimes compared to cathedrals, and when they are, I understand. Compared to some churches I’ve attended, I’ve often felt greater fellowship with strangers and closer to life’s source at ballparks.

After pausing briefly to absorb the scene, we grabbed a seat behind the left field wall. The stadium’s architects—HNTB and Mo and K. Norman Berry Associates—purposefully placed a gently sloping grass embankment within the $40-million facility that opened in 2000 and accommodates 13,000 fans. Families are encouraged to picnic there while enjoying the game. We would stroll to the berm from our box seat and it would become our favorite location that season. That first trip, Hannah spread her blanket, taking care to ensure she’d be leaning against me when she sat down.

We passed a few innings buying concessions from passing vendors. Ice cream from one, a fruit punch from another, later a solitary Budweiser for me. Picnicking in left field, the box seat was long forgotten.

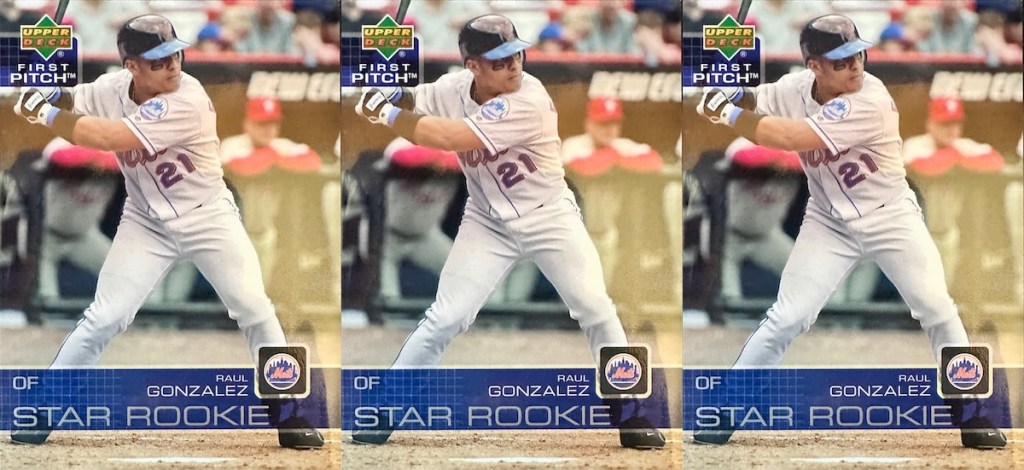

Then Raul Gonzalez came to bat. A 28-year-old native of Santurce, Puerto Rico, the centerfielder came to the Bats via the major league’s Chicago Cubs.

I knew nothing about him, unlike Drew Henson, say, who once led the Michigan Wolverines at quarterback and was now playing third base for the Yankees’ AAA affiliate. Yes, this guy, who was recently just barely beaten out of the Michigan starting QB job by a kid named Tom Brady, was toiling away here in the minors despite having signed a $17-million contract.

Gonzalez, though, was a stranger to me. The scoresheet I’d bought for a dollar told me only that he’d hit .214 for Cincinnati in 11 games the year before.

What was unique about Raul was the way Louisville fans reacted when he approached the plate. They’d yell his name supportively as he settled into the batter’s box.“Rauuulll,” the fans shouted, their earnest way of encouraging the slugger to give one a good wallop.

But then a delayed albeit loud and shrill “Ryooo!” sounded, followed by another. It took a moment, but I found the surprise source sitting on my knee, shouting the hitter’s name in a high, excited voice. Hannah had just started her first sporting tradition, her first stadium eccentricity. More importantly, her joining in celebration with maybe 10,000 others was entirely self-motivated. I hadn’t said anything; I had been busy looking up Raul’s statistics from the previous year. She sounded a third “Ryooo!” then turned to face me, as excited and proud as if she’d just completed her first somersault.

Needless to say, I encouraged her. Her mother would later attend a game with us against the visiting Charlotte Knights, where Hannah enthralled those sitting around us with her version of “Ryooo!”

She made it all the way to the seventh inning that first game. She lasted for a complete game the next time out. Not bad for a kiddo that wasn’t yet three.

We caught a half-dozen games together that summer. At each Hannah’s attention often turned to riding the carousel behind right field, talking me into another Pepsi or box of candy or securing another chocolate chip treat from the Kizito Cooky Lady—a creative and entrepreneurial Ugandan immigrant—who walks the Slugger Field stands balancing an oversize basket packed with large cookies atop her head.

Then the announcer would inevitably call Raul’s name and, with radar-like lock and attention arrested, she’d return to the action at home plate and launch more “Ryooos!”

Subsequently, I was crushed when the Reds called Gonzalez up. I’d no longer be able to hear my daughter’s joyous “Ryooo!” exclamations. But, I was happy for Gonzalez. He’d been posting great numbers and earned the promotion.

Then, as happens in baseball, he was sent back down. He’d hit well with the Reds, but the parent team was apparently just getting him some big league at-bats. He was back for several games. And, soon thereafter, it was over. Raul’s bat proved too good for the International League.

A few weeks after Gonzalez returned, and after he was named the International League’s Most Valuable Player of the Year, I was running errands. With the car’s AM radio tuned to the pregame show for a late August matchup—we were still up a game over the Mudhens so every game mattered—I heard Gonzalez had been traded to the Mets. I was crushed again, yet still happy for the player.

Our loss was New York’s gain. I’m unsure whether Mets fans continued encouraging Gonzalez with shouts of “Rauuulll!,” but I suspect they welcomed him warmly. The last I saw he was batting .333 for them in the bigs.

Leave a comment